Agriculture faces a set of major interrelated challenges in the 21st century: it must achieve global food security, meet high quality and safety demands, reverse degradation of ecological life-support systems, and respond to an ongoing biodiversity crisis. In California, we are evaluating how agriculture can be co-managed to simultaneously secure health, conservation, and food production outcomes. Recent outbreaks of shiga-toxin producing E. coli (STEC), Salmonella spp., and Campylobacter spp. in fresh produce have caused regulators and industry buyers to pressure farmers to change their practices. Many farmers no longer apply animal-based composts to their fields. Moreover, concerns that wildlife host diseases have led to the removal of seminatural vegetation around farms because it is thought to be wildlife habitat. After surveying ~600 California farmers, we found that 40% are removing vegetation due to food-safety concerns. Interviews with growers suggest many do not believe these practices make their food safer, but the pressure from buyers is simply too great to withstand.

Aligning with grower sentiment, we analyzed ~250,000 STEC and Salmonella tests from fresh produce collected across California’s Central Coast and found vegetation removal does not improve food safety. If anything, pathogens increased most on farms that had removed vegetation in the past.

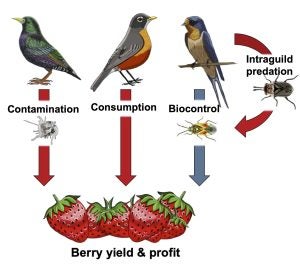

Removing vegetation has far-reaching consequences for the environment and for farmers, beyond any impacts on food safety. We established a network of 27 organic strawberry farms in California’s Central Coast to study how diversifying (or homogenizing) agricultural landscapes affects multiple services and disservices from birds to farmers. Birds can benefit farmers by consuming crop pests, but may also eat beneficial insects, damage crops, or carry foodborne pathogens. Though the net effects of birds on crop yields were fairly neutral, increasing seminatural vegetation around farms was associated with more diverse and multifunctional bird communities that provided more services and fewer disservices. As a result, the net impact of birds on crop yields was more positive on farms surrounded by more seminatural vegetation.

Removing vegetation has far-reaching consequences for the environment and for farmers, beyond any impacts on food safety. We established a network of 27 organic strawberry farms in California’s Central Coast to study how diversifying (or homogenizing) agricultural landscapes affects multiple services and disservices from birds to farmers. Birds can benefit farmers by consuming crop pests, but may also eat beneficial insects, damage crops, or carry foodborne pathogens. Though the net effects of birds on crop yields were fairly neutral, increasing seminatural vegetation around farms was associated with more diverse and multifunctional bird communities that provided more services and fewer disservices. As a result, the net impact of birds on crop yields was more positive on farms surrounded by more seminatural vegetation.

What about the food-safety risks from birds? After combining our pathogen data with other studies in the Western U.S. (~11,000 pathogen tests and 94 bird species), we found that Salmonella and STEC were very rare in birds (0.46% and 0.22% prevalences). Campylobacter was more common (8% prevalence), but actually tended to decrease on farms with more surrounding habitat.

Ongoing Work

Our ongoing work continues to elucidate the food-safety risks of wild birds to guide farming practices. For example, growers are often told to deter all birds and forego harvesting crops near all feces, but our recent work funded by the Center for Produce Safety suggests not all birds and feces pose the same risks. For example, we found pathogen die-off is very rapid in small feces produced by small birds. Since large birds are relatively uncommon on farms, we found that growers could dramatically reduce crop losses by ignoring feces in low-risk contexts (i.e., small feces deposited on soil). Together, these findings related to birds and food safety align well with a broad evidence synthesis that we conducted regarding the efficacy of many food-safety practices. While the efficacy of some practices is well established (e.g., not applying raw manure), other practices like habitat removal are not.

Our ongoing work continues to elucidate the food-safety risks of wild birds to guide farming practices. For example, growers are often told to deter all birds and forego harvesting crops near all feces, but our recent work funded by the Center for Produce Safety suggests not all birds and feces pose the same risks. For example, we found pathogen die-off is very rapid in small feces produced by small birds. Since large birds are relatively uncommon on farms, we found that growers could dramatically reduce crop losses by ignoring feces in low-risk contexts (i.e., small feces deposited on soil). Together, these findings related to birds and food safety align well with a broad evidence synthesis that we conducted regarding the efficacy of many food-safety practices. While the efficacy of some practices is well established (e.g., not applying raw manure), other practices like habitat removal are not.

Unrelated to food safety, we are also excited about a new large experiment that seeks to explore strategies for bolstering biodiversity and ecosystem services in California rice. Rice farmers often flood their fields in winter, supporting millions of migratory waterbirds and other wetland-associated wildlife. Yet growers are beginning to search for alternatives to winter flooding, as climate-induced droughts increase water prices and regulators begin to scrutinize greenhouse gas emissions emanating from flooded fields. Our USDA-funded project seeks to determine whether introducing fish onto rice farms represents a viable path forward for incentivizing winter field flooding. Specifically, by excluding waterbirds and adding fish to industrial rice fields, we aim to advance our understanding of how birds and fish interact and what those interactions mean for weed control, nutrient cycling, crop yields, and greenhouse gas emissions. Check out this recent video on out work: